Early Attempts Against CW

The video lecture covers the following topics:

- reference to early cultural interdictions

- reference to the Hague Peace Conference of 1899

- 1925 Geneva Protocol (G), and explanation of its impact on future norm building

Early Constraints on Chemical Warfare

Early bans on poisoned weapons

The Manu Smrti, a foundation of Hindu law, contains the earliest recorded prohibition on poison (G) use. It is over 2,000 years old. History also shows that cultures in different parts of the world adopted similar codes. However, the unilateral codes did not bind the enemy.

Religions opposed indiscriminate warfare, which is the root of the interdiction on poisons. In Islam it evolved from the prohibitions on flooding and fire in the 10th century. Christianity began framing similar codes in the Middle Ages. However, they applied only to one’s own religious community. The Diaspora prevented Judaism from developing similar rules.

With the rise of the sovereign state, formal codification of the rules of war began in multilateral conferences in the 2nd half of the 19th century. The industrial revolutions also generated the first interest in arms control, but constraining technology was an idea whose time had not yet come.

First Hague Peace Conference

Fearing the impact of the industrial revolution on armaments, Russia, an agrarian society, convened the 1899 Hague Peace Conference. The meeting failed to limit armaments, but with the Convention (II) and annexed Regulations it codified the laws and customs of war on land. The document included an overall ban on the use of poison and poisoned weapons.

In recognition of technological progress, the Conference also concluded Declaration (IV, 2) Concerning Asphyxiating Gases outlawing the use of projectiles designed to diffuse asphyxiating or deleterious gases. The focus of the regulation, however, was on ‘use’, not the weapon as such.

The 1907 Hague Conference updated the Convention with its Regulations, but maintained the Declaration on asphyxiating gases. Most independent states at the time signed up to the document.

In 1915 the first gas attack circumvented the prohibition because gas cylinders rather than projectiles were used.

The Geneva Protocol

The 1925 Geneva Protocol (G) prohibits chemical and biological methods of warfare (G). It is a direct descendant of the 1899 Hague Declaration (IV, 2) and the 1919 Versailles Treaty banning Germany from using CW.

Even though never violated for biological warfare, at several occasions it could not prevent CW use. However, each time nations came together to renew their commitment to the agreement. Thus it gradually became part of customary law and is now seen as universally binding and applicable to any type of armed conflict.

Today it offers the legal foundation for the UN Secretary-General’s Mechanism to investigate allegations of use. Its language has also been incorporated into the 1998 Rome Statute (G) that established the International Criminal Court. Both instruments will be discussed further in the chapter.

The Chemical Weapons Convention

The video lecture covers the following topics:

- Chemical Weapons Convention (G) and the role of the OPCW (G)

- General Purpose Criterion (G)

- OPCW, structure and division of labour with States Parties (National Authorities)

- verification (G) and compliance machinery

- decision-making process, including review conferences (G)

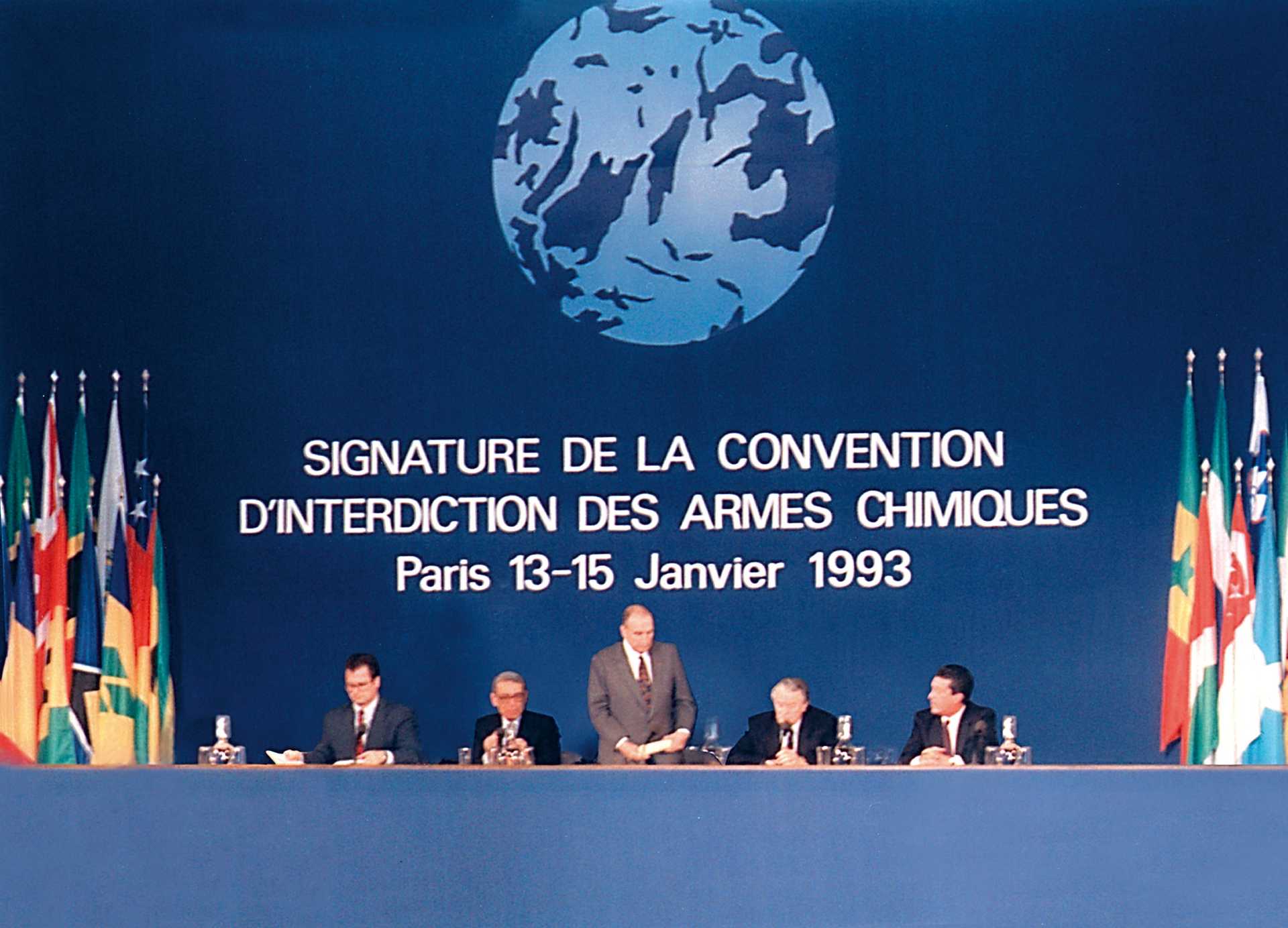

The CWC (G) was opened for signature in 1993 and entered into force in 1997. It established the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), which is based in The Hague. All states parties are member of the OPCW and have equal rights and obligations. The OPCW (G) oversees treaty implementation, organises verification and ensures compliance. To these ends it is supported by the Technical Secretariat with its inspectorate.

One of its principal tasks has been verifying (G) the destruction of CW. Eight states declared 72,525 metric tonnes of agents and 8.67 million items, including munitions and containers. At the 24th Conference of the States Parties (25-29 November 2019), the Technical Secretariat of the OPCW reported that as of 31 December 2018, 96.72% of warfare agents and precursor chemicals were destroyed under international supervision. Destruction operations are expected to have been completed by 2023 at the latest. The OPCW is now increasingly focussing on the prevention of the re-emergence of CW and new challenges, including scientific and technological innovation, chemical security, and outreach to professional communities.

Universalisation (G)

Opening for signature (1993)

As of July 2021, the CWC comprises 193 states parties. With this it is the world’s most successful weapon control treaty. Only four states still need to ratify or accede to it: Egypt, Israel, North Korea and South Sudan.

General Purpose Criterion

The CWC does not prohibit toxic substances as such, but outlaws purposes to which they may be applied. Known as the ‘General Purpose Criterion’ (GPC) (G), the principle is contained in Article II of the CWC. Many toxic chemicals have legitimate industrial applications. In this way the CWC not only addresses the dual-use problem, but also covers any future toxic chemical.

Reinforcing the Norm against CW

While the CWC (G) and the Geneva Protocol (G) form the backbone of the norm against CW today, the international community has devised other instruments to support it. As has been the case since the late 19th century, security challenges evolve faster than the codification process.

The new tools are often action-oriented: they are the responsibility of individual states and implementation objectives are set against concrete timelines. Other characteristics often include the informality of the arrangement, the formation of a coalition of like-minded states, and the absence of lengthy, formal negotiations to set those instruments up. Another trend is the rising prominence of humanitarian and human rights law with the attendant focus on criminalising individual behaviour under international law.

The tools presented on this page are four among many initiatives launched or reinforced since the end of the Cold War.

Australia Group

The AG is an informal grouping of 42 states and the EU that aims to counter the spread of technologies and materials used for chemical and biological weapons through coordinated export controls, information sharing and outreach. It reviews its technology control lists at its annual meetings.

It was originally created in 1985 after UN confirmation of Iraq’s CW use the year before.

UNSG’s Investigative Mechanism

The UN Secretary-General’s investigative mechanism evolved from the investigations into Iraq’s violations of the Geneva Protocol between 1984–88. Formalised by UN resolutions, it allows the UNSG to dispatch fact-finding missions after a UN member request.

Regarding CW, the UNSG now draws on OPCW expertise in case of alleged use by or in a non-CWC party. For BW cases, he maintains a roster of national experts.

UNSC Resolution 1540 (2004)

After 9/11 the Security Council voted several anti-terrorism resolutions, including 1540 (G) that aims to prevent terrorist acquisition of nuclear, biological and chemical weapons. All UN members must adopt and enforce, as well as report to the 1540 Committee on appropriate national legislation.

Regarding CW, the obligations parallel those of Article VII of the CWC, but they apply to all UN members.

The 1998 Rome Statute and the ICC

The Rome Statute (G) defines CW use as a war crime in both international and internal conflicts. The Hague-based International Criminal Court can pursue such violations if national courts are unwilling or unable to try criminals or after UNSC referral.

The Rome Statute utilises the language of the Geneva Protocol and does not refer to the CWC or BTWC (G), as some countries wished to avoid any references to nuclear weapons.