Key Terms and Concepts

Peace Delegates on NOORDAM - Mrs. P. Lawrence, Jane Addams, Anna Molloy.

Two approaches to Gender and disarmament

In this video you will learn about key concepts such as:

- difference between sex and gender

- creation of gender norms

- What is gender mainstreaming and what tools could be applied to a gender mainstreaming approach?

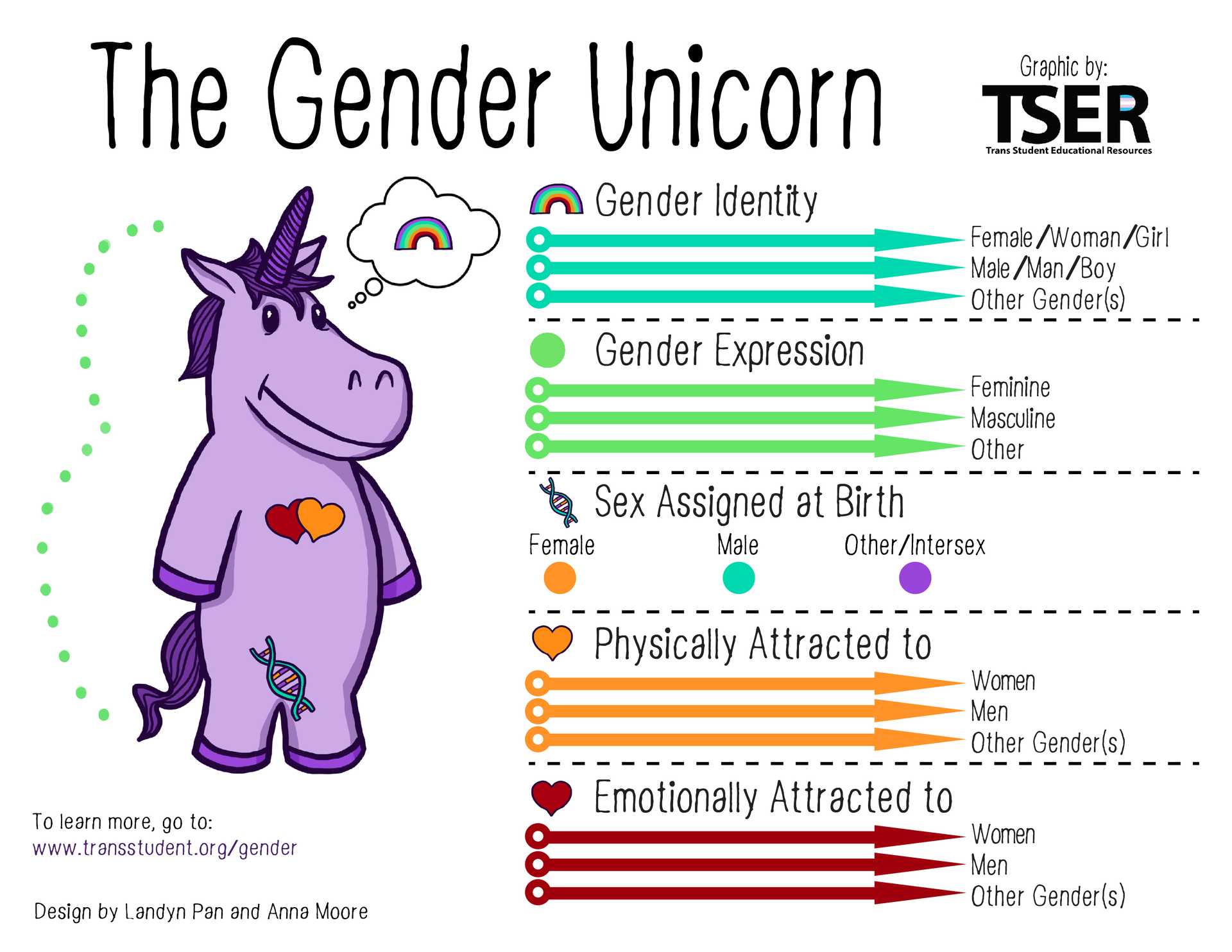

The Gender Unicorn

What ist Gender?

The Gender Unicorn offers a sliding scale, not a checkbox, on individual identity and the difference between gender, sex assigned at birth and sexuality.

Gender ≠ Sex Assigned at Birth

-

Gender Identity: an individual’s internal sense of being female, male or other

-

Gender Expression: the physical manifestation of an individual’s gender identity, e.g. through clothing, hairstyle, body shape

-

Sex Assigned at Birth: the classification and assignment of an individual being female, male or other/intersex based on biological and physical characteristics such as anatomy, hormones and chromosomes

Zooming in on Gender Mainstreaming

Gender mainstreaming helps bring a gender perspective into policy making. The video produced and kindly provided by the European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE) helps explain this concept highlighting two main dimensions:

- Gender Responsive Content of Policies

- Gender Representation in Policy Areas

To understand how this relates to disarmament note that:

- Gender norms shape how weapons are seen and used in society and their impact.

- Gender analysis can increase understanding on how arms control and violence impact all sectors of society.

- Collecting sex disaggregated data aids in gender analysis to better understand the impacts of weapons on society and the needs of different individuals and groups.

- Women are underrepresented in fora focused on peace and security. Gender balanced representation is a means to improve policy and decision-making in this regard.

This video covers the history of women’s movements advocating for peace and disarmament. The video features key historical examples, such as:

- The Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF)

- The Nuclear Protests at Greenham Common Military Base in the UK

- The Liberian Women’s Initiative

Case Study: WILPF

In 1915 women came together to try to stop the Great War. A group of over 100 women from warring and neutral nations gathered at the first Women’s Congress in The Hague on 28 April 1915. The outcome of the Congress was 20 resolutions at the core of which proposed mediation as an alternative to armed conflict and promoted women’s participation in international discussions and post war settlements. Another outcome was the creation of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom which still exists today and now has a dedicated disarmament programme called Reaching Critical Will

First Meeting of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom in 1915.

Case Study: Greenham Common

- Started in 1981 when the Welsh group “Women for Life on Earth” marched to the Royal Air Force base at Greenham Common in England.

- Group members chained themselves to the fence of the airbase to challenge the government’s plan of placing 96 cruise missiles on the base.

- When the government ignored the action, a peace camp was set up outside the base and was active for almost two decades.

- After the US and Soviet Union signed the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty in 1987, the last cruise missile was removed from Greenham Common in 1991.

I only meant to protest at Greenham nuclear base for a week, but ended up living at the Women’s Peace Camp for five years. (…) Together we encircled the 9-mile perimeter fence, covering it with family photos and messages of fear, love and hope, showing why we wanted to prevent war.

Please read the full eyewitness testimony written for this eLearning unit by Dr. Rebecca Johnson who lived at the Greenham Women’s Peace Camp from 1982 to 1987.

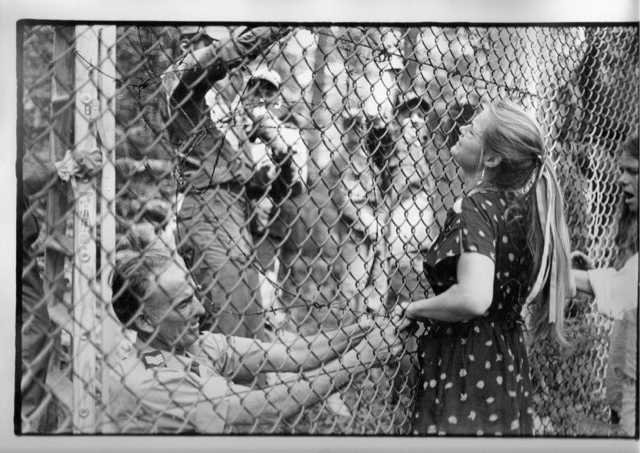

Dr Rebecca Johnson in July 1983 at the Greenham Common fence as more rolls of barbed wire are being put up.

Greenham Women’s Peace Camp: a groundbreaking ecofeminist campaign to prevent nuclear war

By Rebecca Johnson

In the early 1980s, new types of nuclear weapons made many people wake up to the risks of nuclear extinction, as over 50,000 nuclear warheads waited for someone to make a mistake. People respond to fear in different ways. Going to the Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp was my way to stop having nuclear nightmares.

NATO had designated the US Airforce base at Greenham Common to receive 96 nuclear armed cruise missiles in a ‘dual track’ decision to counter Soviet SS20s with US ground-launched cruise and Pershing II missiles targeted at Russia. Greenham was 60 miles West of London, near the UK’s Aldermaston nuclear bomb factory. On 5 September 1981 the British government ignored 33 ‘Women for Life on Earth’ who had walked from Cardiff in Wales to the USAF base in Berkshire calling for a public debate on these new nuclear deployments. So they pitched a peace camp in front of the base.

I only meant to protest at Greenham nuclear base for a week, but ended up living at the Women’s Peace Camp for five years until US President Reagan and Soviet General Secretary Gorbachev signed the 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty.

Our campaign hit the headlines when 35,000 women came to Greenham to ‘Embrace’ and ‘Close’ the base on 12–13 December 1982. Together we encircled the 9-mile perimeter fence, covering it with family photos and messages of fear, love and hope, showing why we wanted to prevent war. Then we blockaded all the entrances to halt work on the nuclear silos. This was achieved despite some of us being sent to prison for 14 days under a ‘breach of the peace’ law that dated back to the year 1361.

1983 was the most extraordinary year, marked by the arrival of cruise missiles at Greenham just weeks after NATO’s ‘Able Archer’ military exercises nearly ignited nuclear war. On New Year’s Day 44 women climbed on top of the nuclear silos and media sent pictures of us dancing around the world. More imprisonment, more actions, at Parliament and Downing Street. In May we mo-bilised a million women to become ‘Greenham Women Everywhere’ and oppose nuclear weap-ons all over the world. We then launched a federal court case in New York to prevent the US deployment of cruise and Pershing II in Europe.

It didn’t succeed. The first cruise missiles were flown into the base in November 1983, and our nonviolent protests were met with escalating state violence from then on. In response, 50,000 women used our hands and voices to remove over half of the military perimeter fence in Decem-ber. As 1983 ended, three Greenham women occupied the air traffic control tower for over five hours with a huge Christmas banner proclaiming ‘Peace on Earth’.

By 1984, rainbow coloured camps stretched all around the Greenham base. At the heart of each was the fire, with blackened kettles and heated discussions. Our lives were punctuated by ar-rests, evictions and imprisonment. When police and bailiffs forcibly evicted us, tore down our shelters and extinguished our cooking fires we always returned, relit the fires, sang our songs and made more plans and cups of tea.

When the cruise missiles were taken out on their massive ‘transporter-erector-launchers’ to ‘melt into the countryside’ (as military planners said), we developed local ‘Cruisewatch’ networks and continued to challenge, block and demoralise the biggest military establishment in the world.

Greenham Women Everywhere connected with peace camps and protests in other countries and became a powerful inspiration for generations of women who love life and work together in all our diverse ways for a future free of personal and political violence. As ecofeminists we in-sisted that the personal is political and everyone has the power and responsibility to make the world better. Spiderwebs became the symbol of our feminist philosophy that connected our fragile lives to weave new ways to prevent violence and war.

Our lives of nonviolent protest grew into a powerful, creative crucible that also challenged and changed prevailing expectations of peace activism and sexual politics. Learning from survivors of patriarchal violence and wars, we can be found in many different campaigns against the rac-ism, colonialism and sexual violence embedded in patriarchal institutions and militarism of all kinds.

From nuclear weapons to climate destruction, the military-industrial philosophies and practices of patriarchal dominance have brought humanity to the brink of extinction. Greenham’s legacy and feminist-humanitarian ideas also helped to build the International Campaign to Abolish Nu-clear Weapons, which grew out of the connections between activists, doctors, and the Japanese Hibakusha and indigenous people who campaigned so long to ban nuclear weapons, from their production and testing to their use and threats. The Greenham spirit lives on whenever we are together, and wherever fierce young activists campaign for climate action and liberation from misogyny, racism and the crushing weight of patriarchal violence, inequalities and injustice.

By 1992 the missiles and USAF had departed from Greenham. As the INF Treaty emptied the nuclear silos, Greenham Common was restored for local people and nature. On 22 January 2021, the world marked a new milestone as the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) became international law.

Case Study: Greenham Common – Before and After

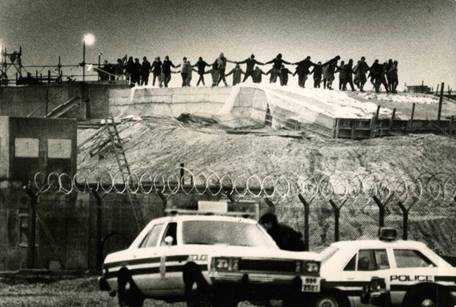

Greenham Common women dance on cruise missile silos New Year Dawn 1.1.1983.

The juxtaposition of these two images shows the powerful impact of the Women’s Peace Camp at Greenham Common. The image on the left captures the 44 women who climbed on top of the nuclear silos opposing nuclear weapons and the arrival of the cruise missiles at Greenham Common in 1983. After 1983 the Women’s Peace Camp continued to grow in numbers, voices and strength, as well as unwavering spirit. The movement rejoiced at the signing of the 1987 Intermedia-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty which resulted in the emptying of the nuclear silos from Greenham Common. The land was restored to the local people and nature, as the photo on the right clearly exemplifies.

Empty nuclear silo at Greenham Common after the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty was signed.

Two Approaches to Gender and Disarmament

In this video you will learn about the two main approaches to gender and disarmament and how they evolved.

- Promoting gender equality and improving women’s meaningful participation in arms control, non-proliferation and disarmament fora.

- Applying a gender lens to disarmament and looking at the impact of weapons and disarmament on women.